Santa Giustina was closed when I got there. That's the thing you need to prepare yourself for when travelling anywhere in Europe, especially in Italy and Spain. Random closures at what you would expect to be prime time. I was a little bit pissed off. I'm nursing an achilles injury and it hurt like hell. I'd walked. A lot. I'd passed up the Scrovegni Chapel, major tourist points. I'd put off drinking Aperol and eating pizza.

That's when I spotted them. A group of middle aged Italians milling around one of the doors. Remember I said Italy is the Saudi Arabia of Christianity? Well, here it is, the Catholic version of the Hajj. Pilgrims. They were going to be my ticket in.

I hung around the back of the group and sure enough, the door swung open. We're in! I have to admit it, I was shitting it. I was the youngest person there by a long way and I'm in my 40's. I stood out like a banana on a calvary scene. I kept thinking, any minute now and the Catholic Security Service is going to pounce on me. Brass it out, Peachy. They swarmed round a desk selling votive cards. That was my chance, make a break for it, go deep and by the time anyone notices I'll have seen half the place at least.

It worked. It worked well. In fact, I had the parts I wanted to see to myself. At the far end of the abbey complex is the oldest part that dates back to the Roman times. Giustina was your standard high-born, beautiful Roman girl who'd taken to Christianity via Saint Prosdocimo (whose tomb is also here). Augustus Maximian, co-emperor and accomplice to the sociopathic Diocletian, took a shine to her and the story played out like hundreds of others. Giustina was having none of it so Maximian put a sword through her chest. A Veronese painting showing the scene is housed in the church. Giustina would eventually be avenged. In 310AD, Maximian made a fairly stupid decision to kill Constantine the Great. Constantine "strongly suggested" (ahem) that he choose suicide. Which he did.

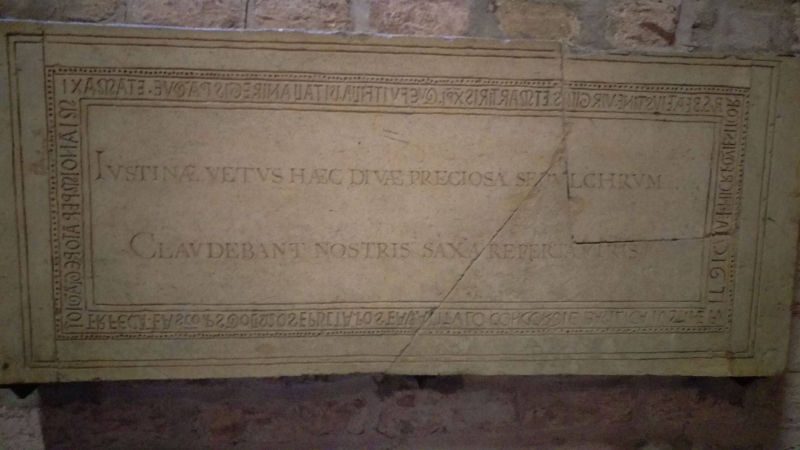

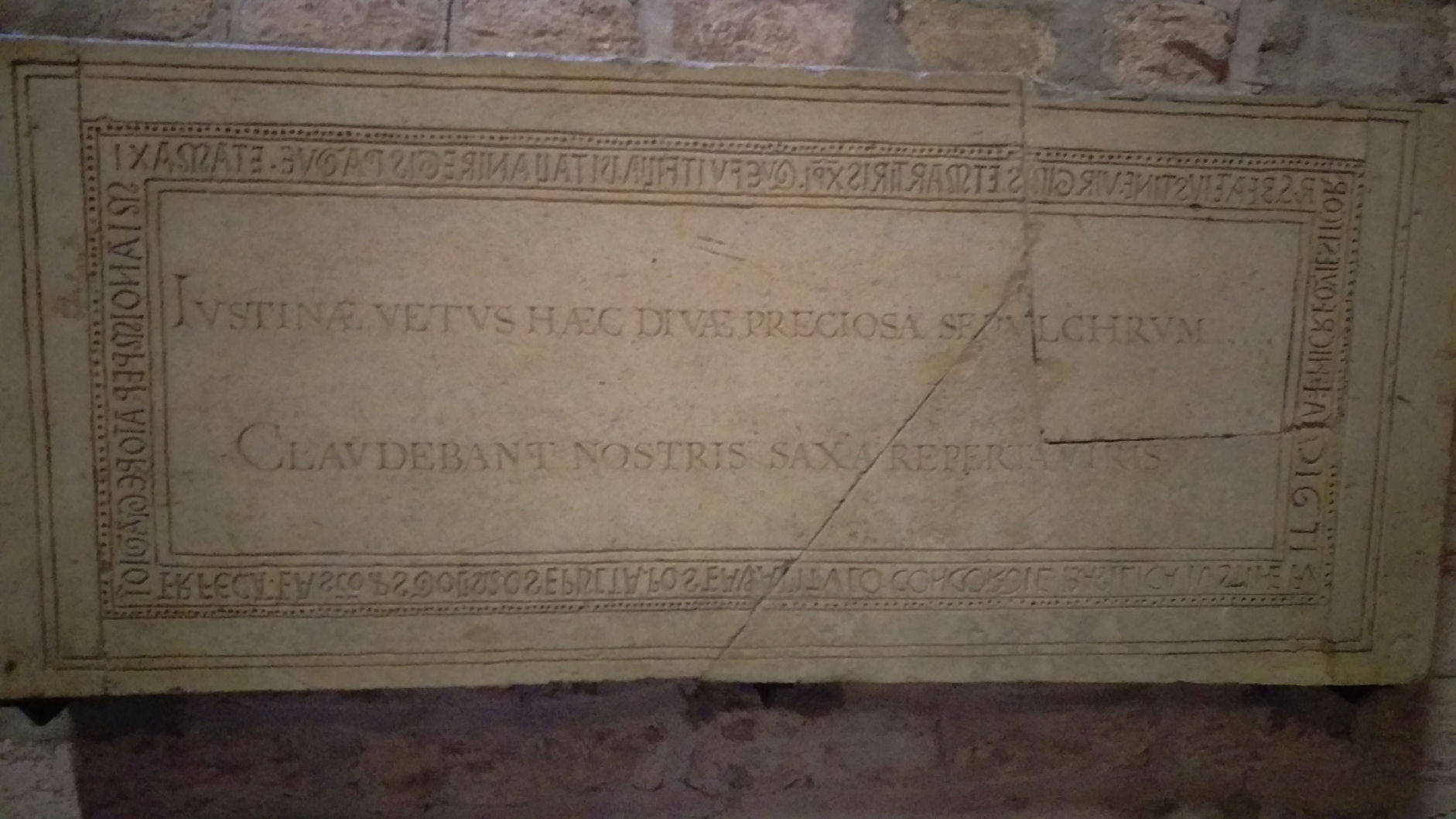

A church grew up around Santa Giustina's tomb in the 600's, now just a simple marble slab in the floor. There are Roman mosaics on display nearby which show that this spot was in use for a hell of a long time. On the way to the old, original part of the complex is the Well of the Martyrs. It sounds like it should be something from an Indiana Jones film or a Dan Brown novel. But peek through the grating in the marble lid and you'll see the bones of more victims of Diocletian and Maximian's persecutions. How they ended up down a well or how anyone found them is a mystery to me but you can't beat a good relic.